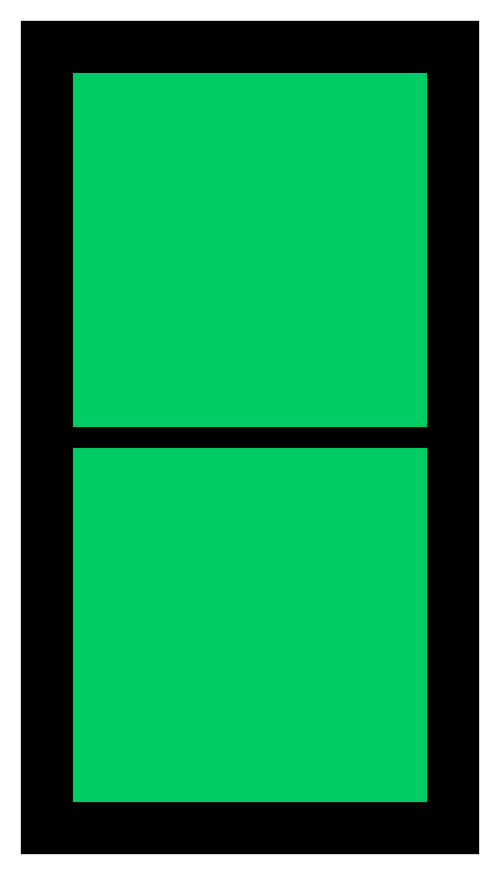

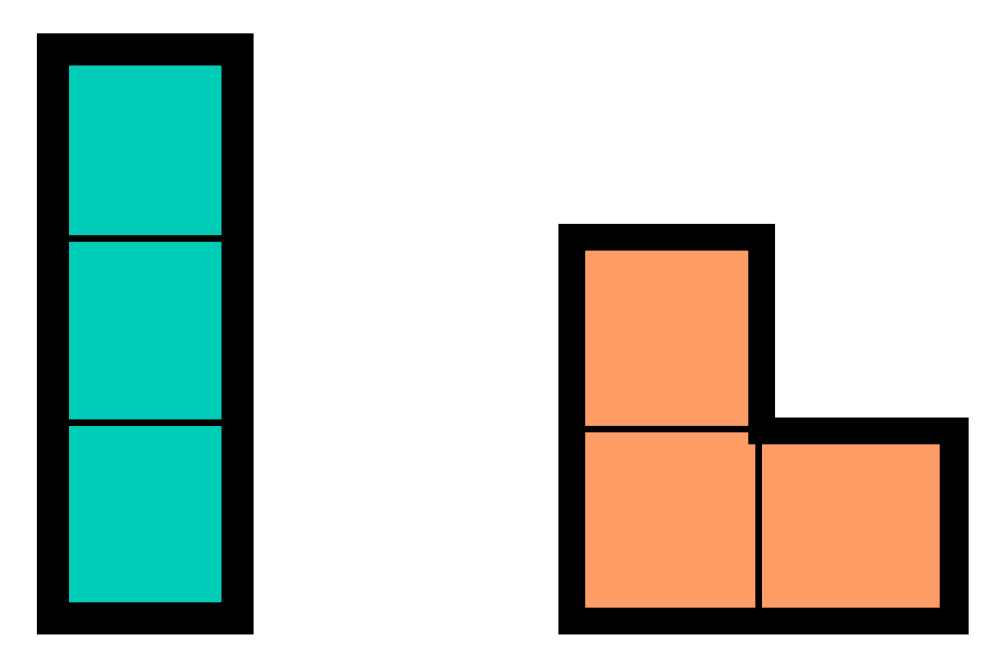

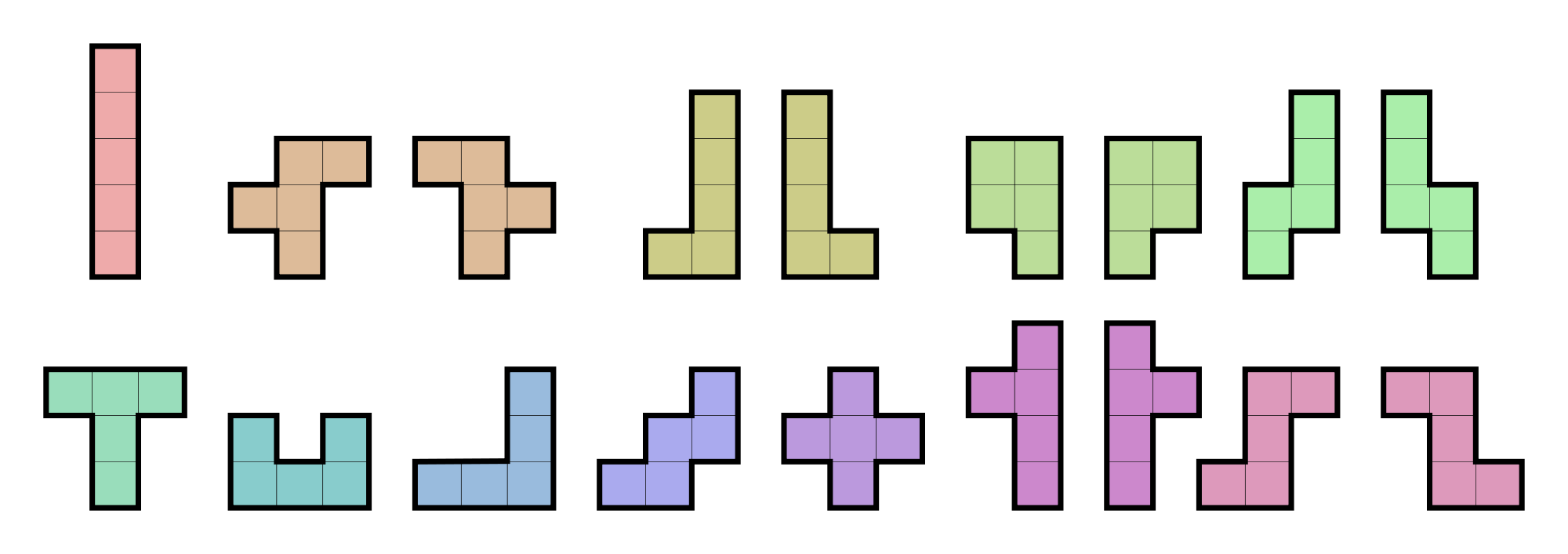

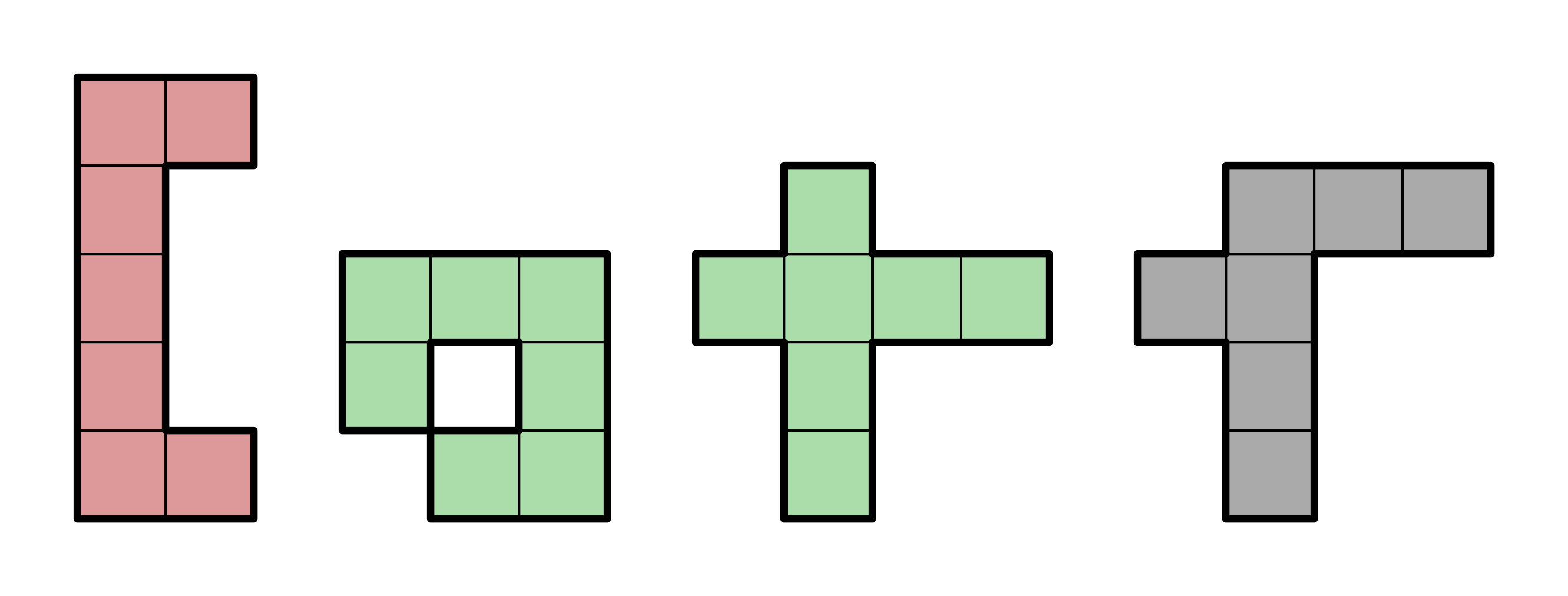

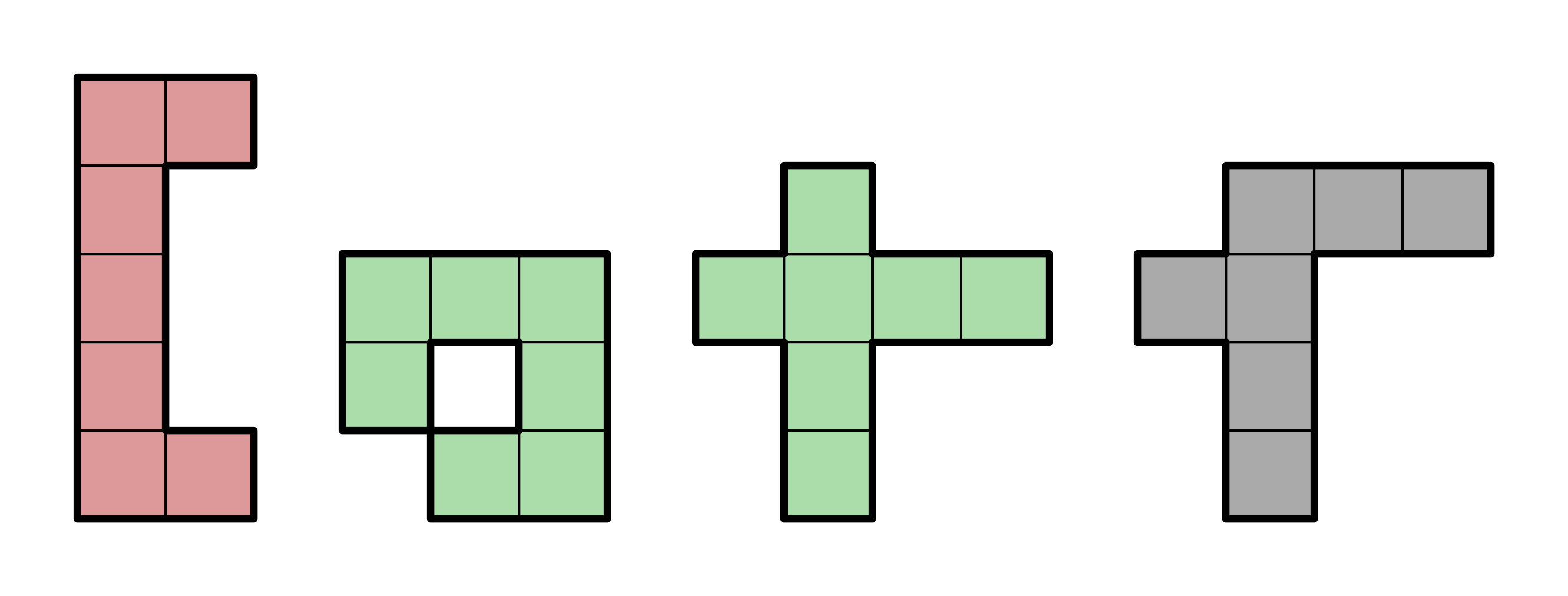

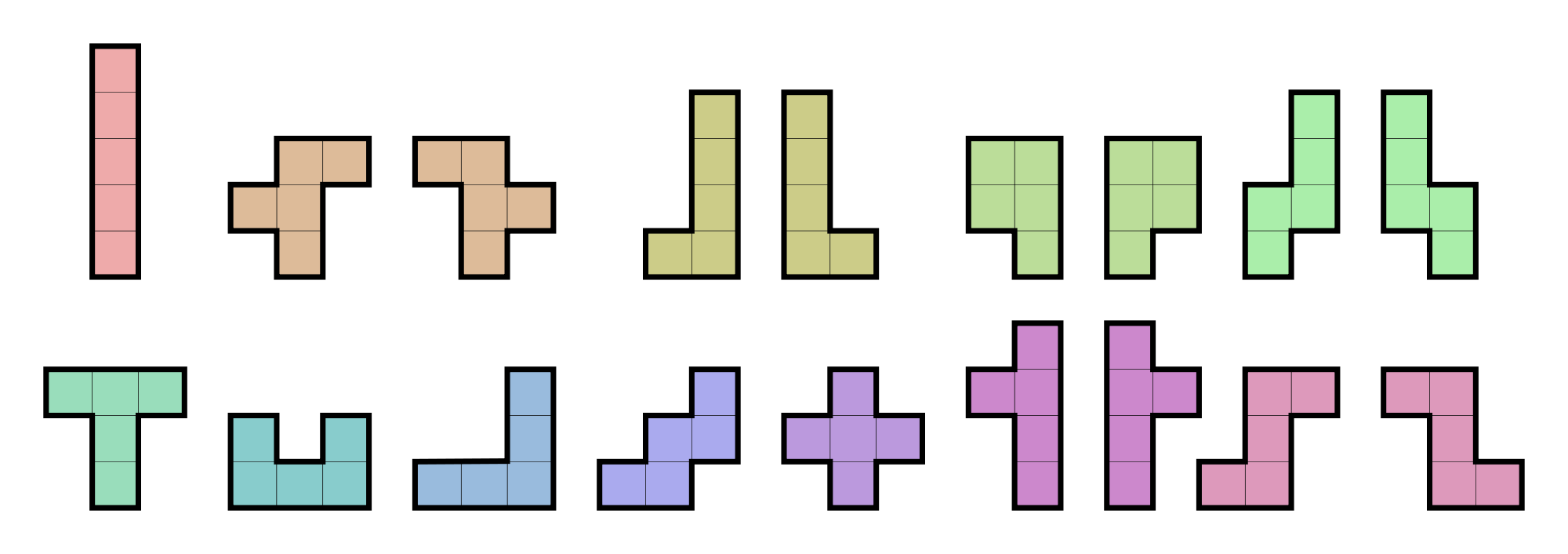

You can think of words as Tetris pieces.

Ashley Bischoff

(You can move between slides with the arrow keys.)

How do I know if my writing is complicated?

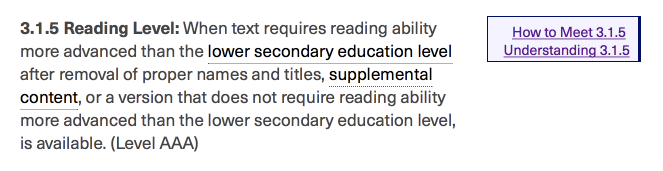

For example, here’s a terrible sentence from 3.1.5:

Readability formulas are available for at least some languages when running the spell checkers in popular software if you specify in the options of this engine that you want to have the statistics when it has finished checking your documents.

The more complex the material, the shorter the sentences should be.

You also want variety.

You should have a few 35-word sentences and some 3-word sentences.

That terrible sentence from WCAG 3.1.5 is easier to read once it’s split into smaller sentences:

Readability formulas are often available when running the spellchecker in your word processor.

You can specify options to show those statistics when it’s finished checking your document.

Sentence length is half the battle.

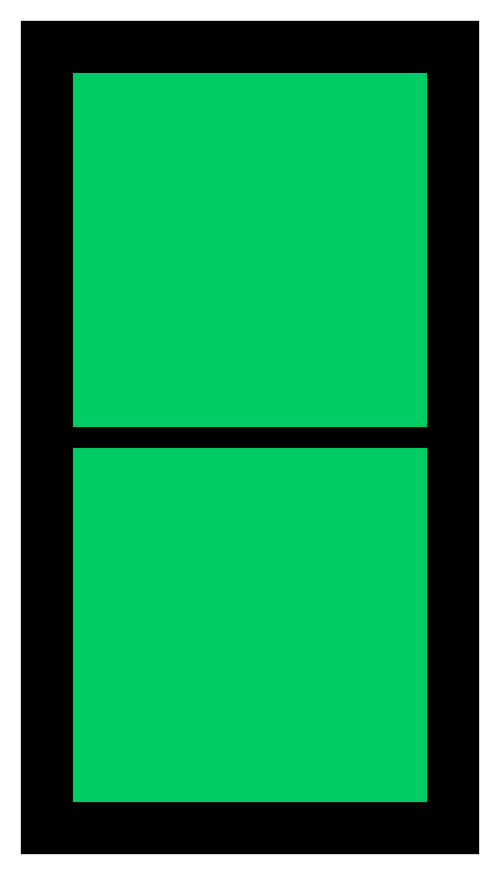

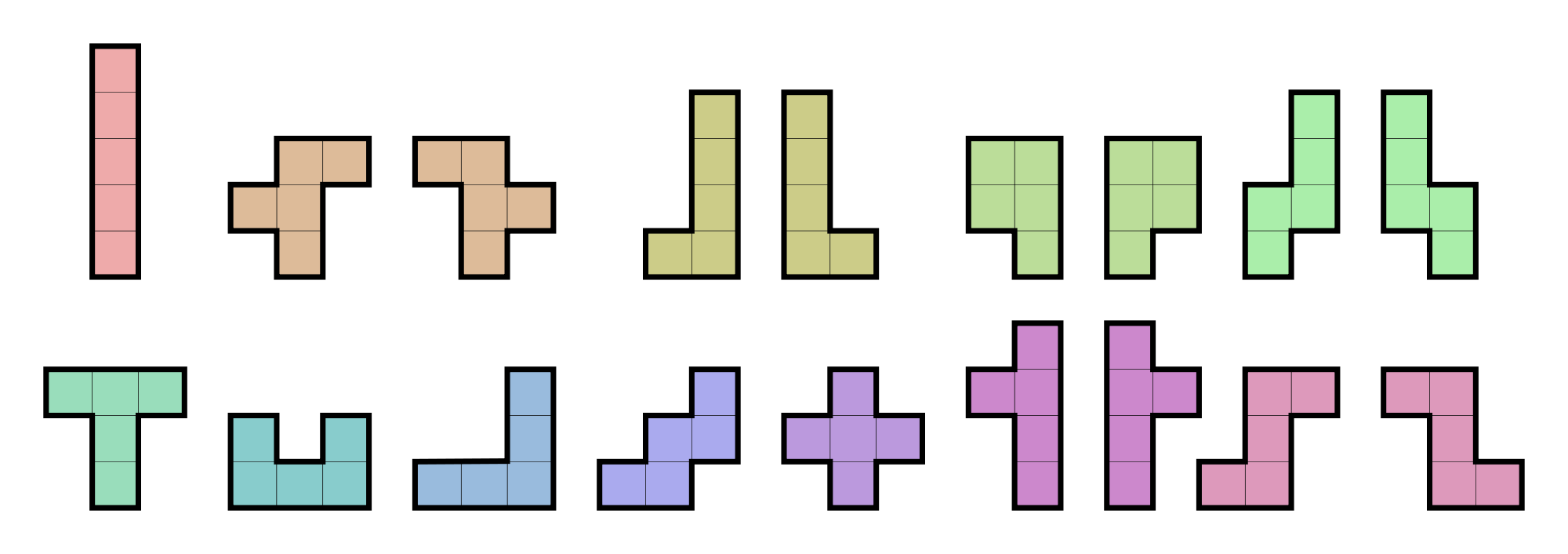

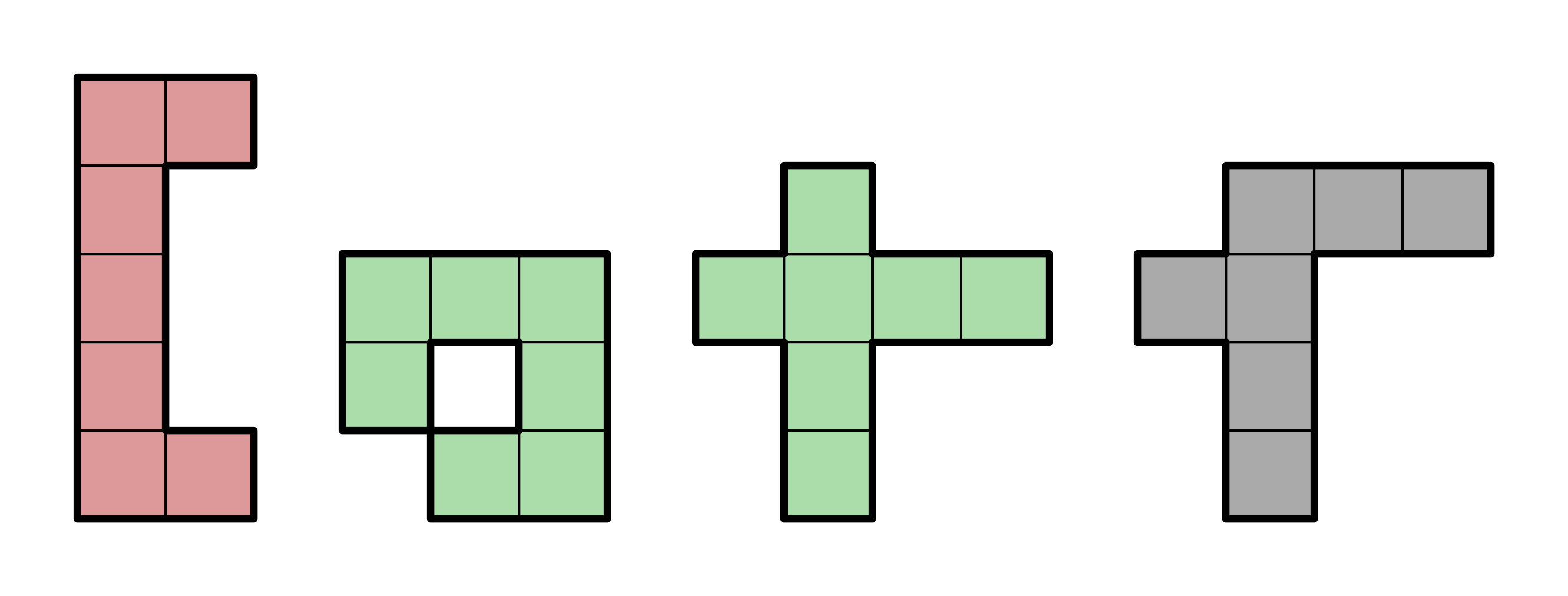

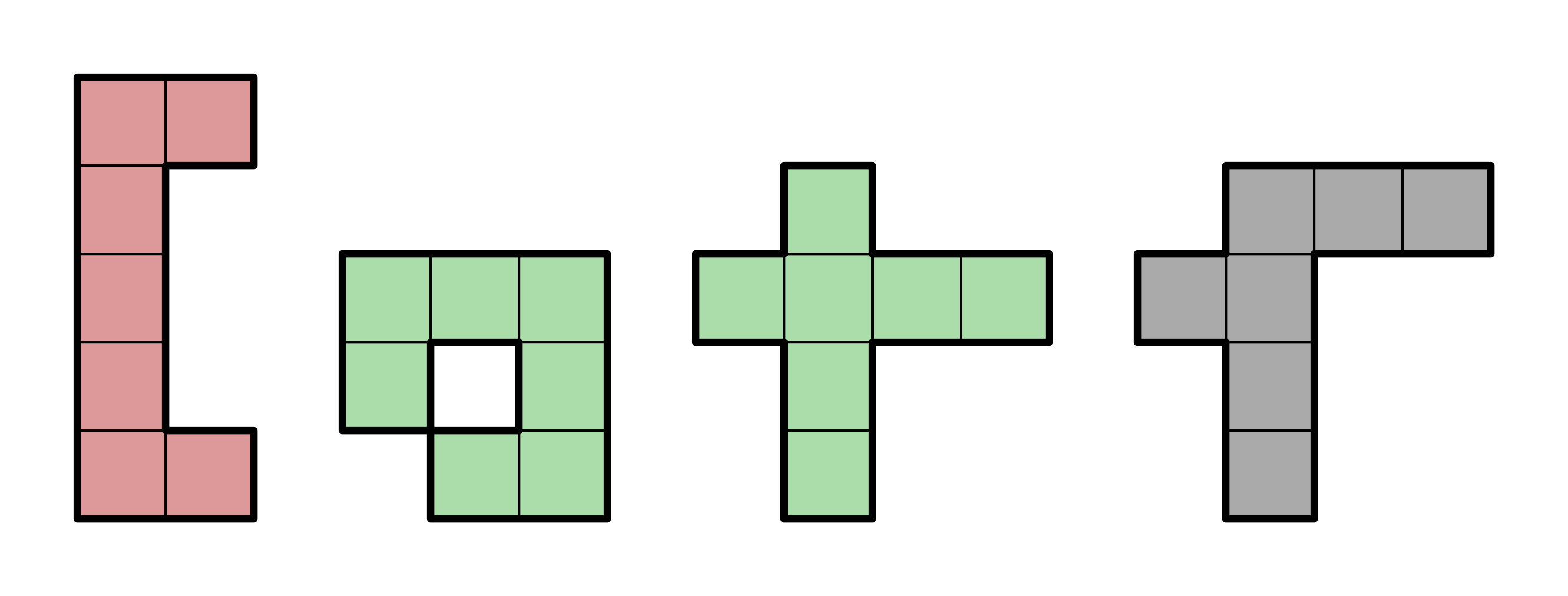

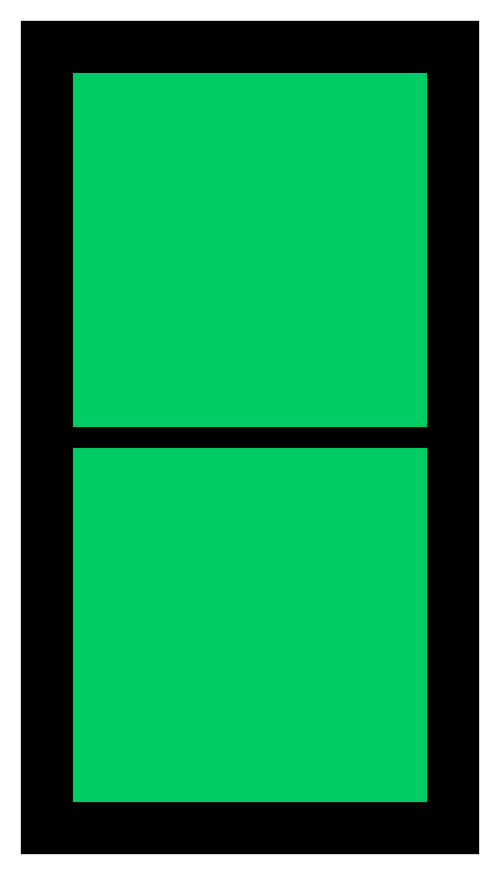

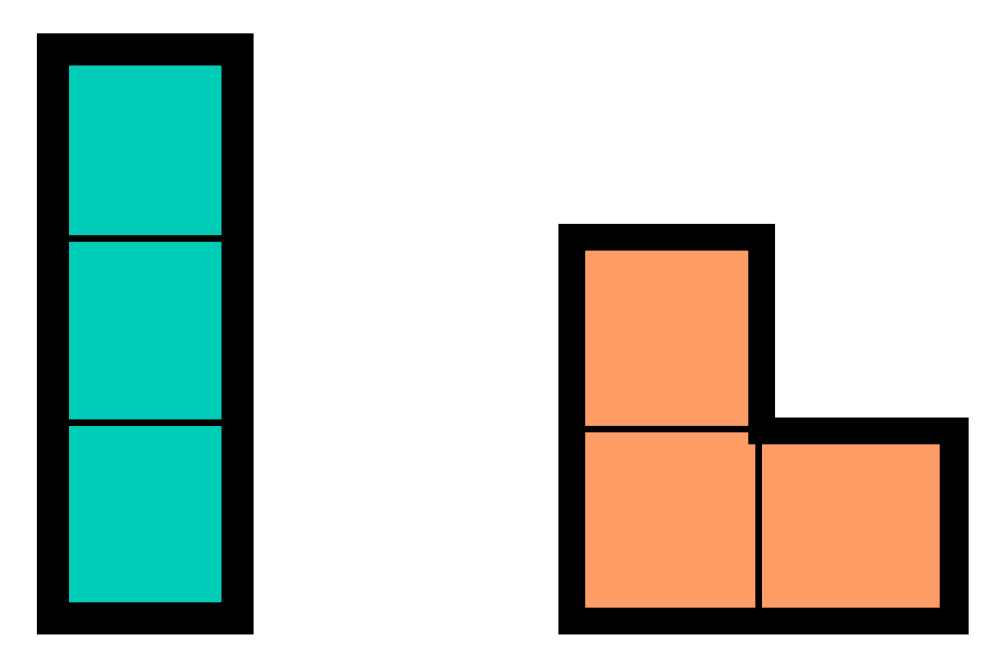

You can think of one-syllable words (such as “so”) like 2-block Tetris pieces.

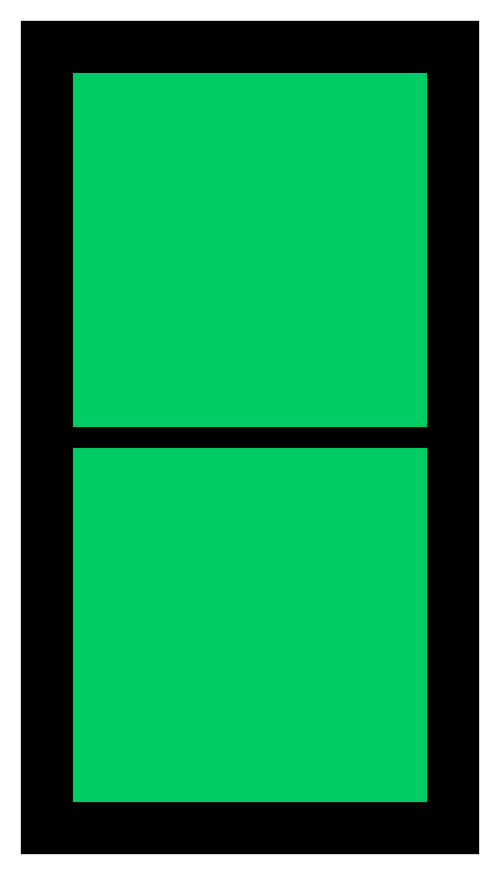

And you can think of two-syllable words (such as “update”) like 3-block Tetris pieces.

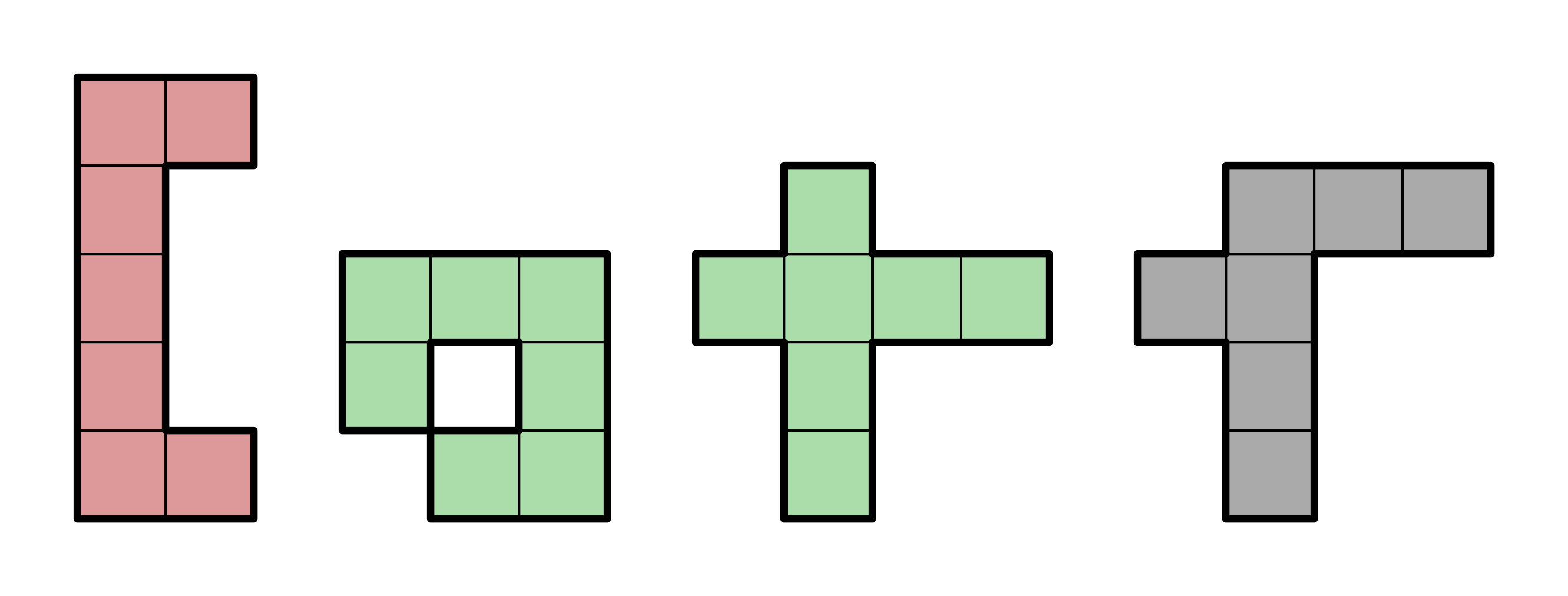

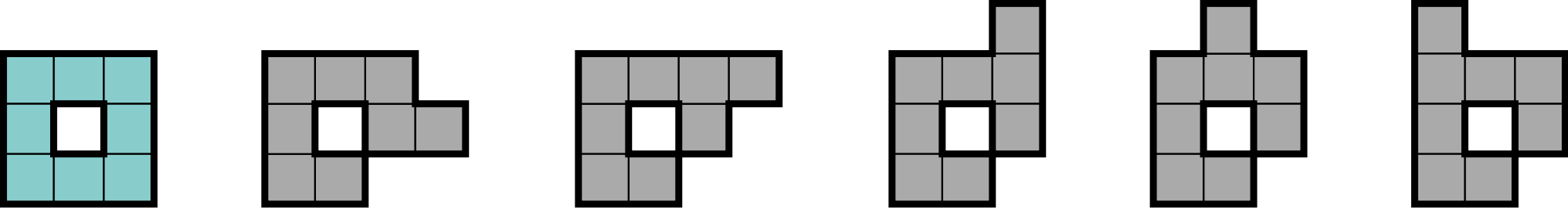

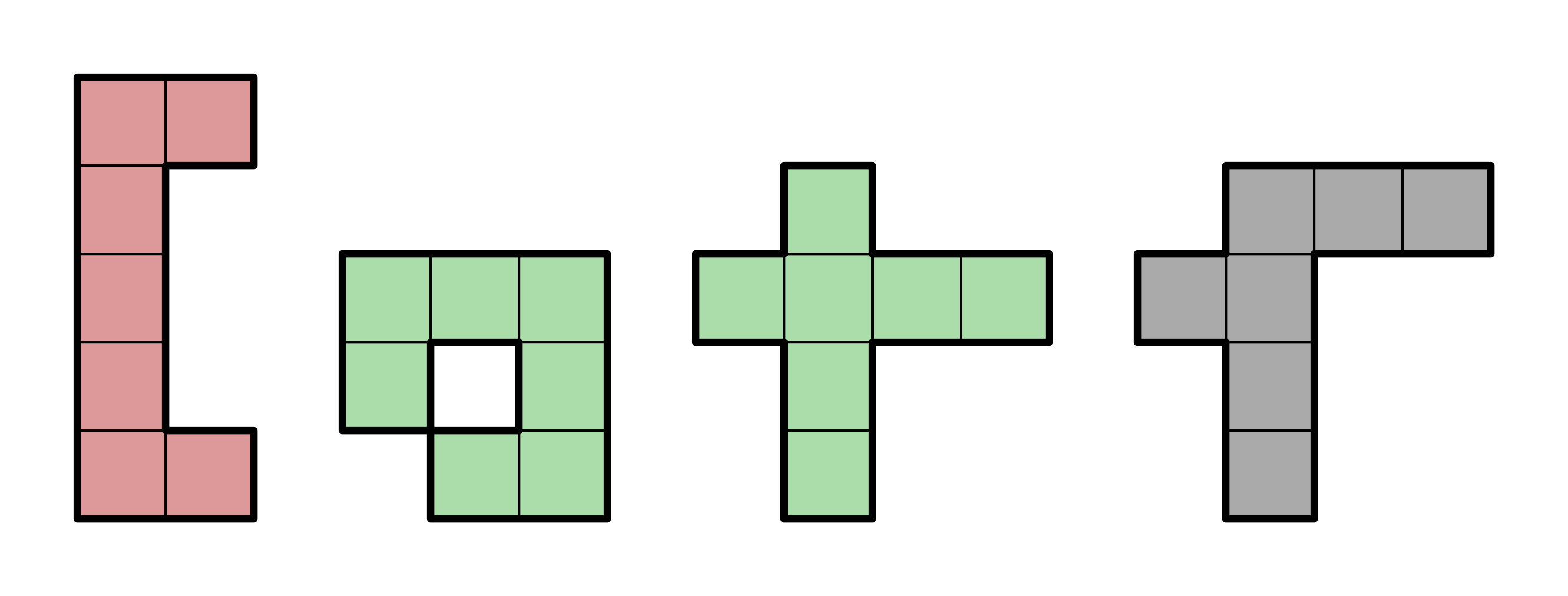

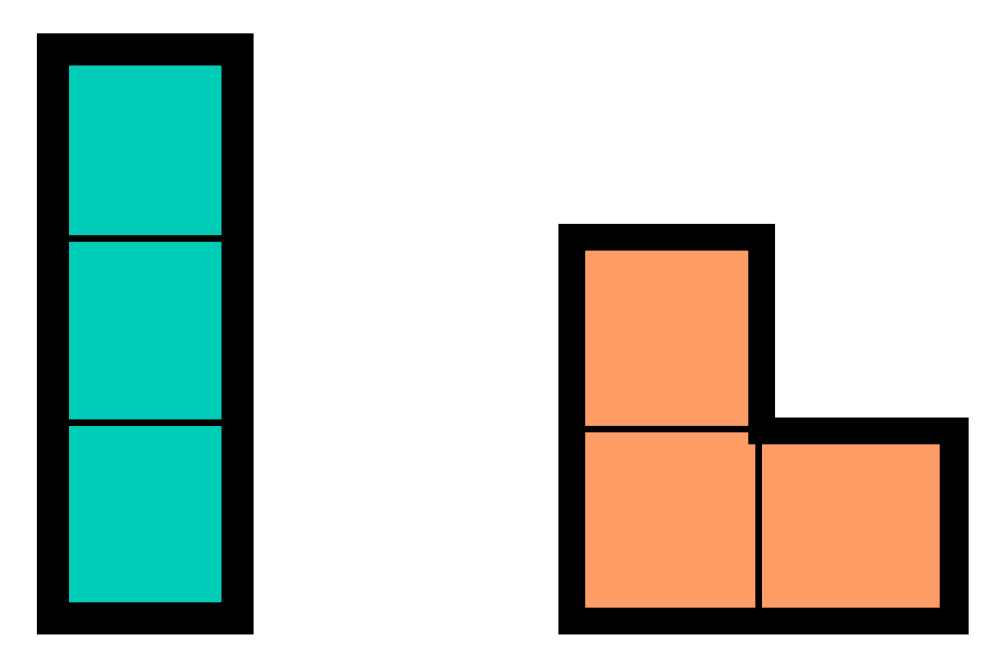

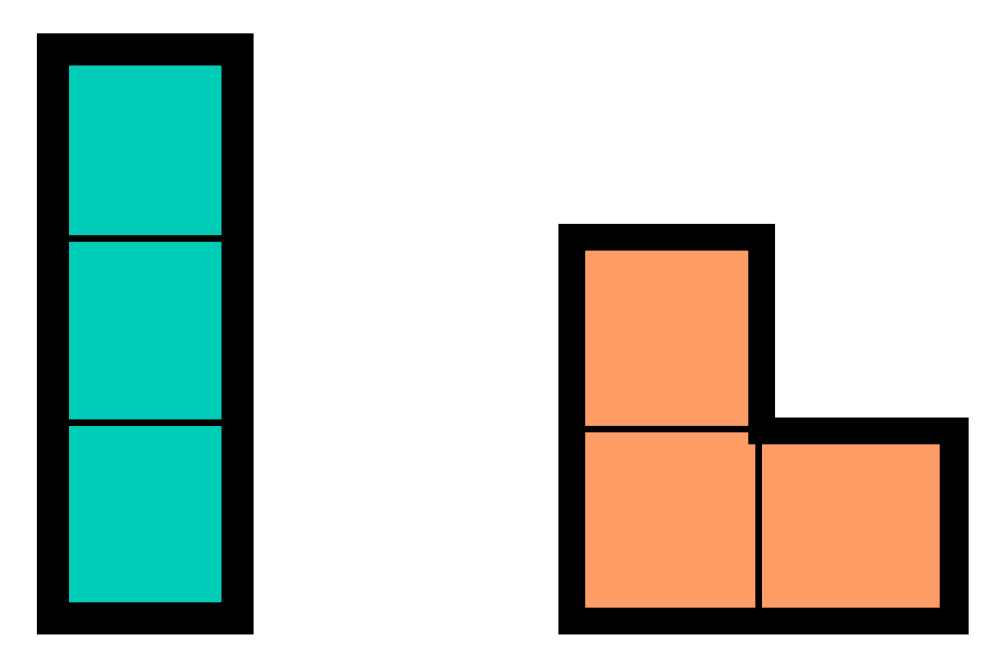

Things start to get a bit tricky with three-syllable words, which amount to 5-block Tetris pieces.

And four-syllable words, which are like 7-block Tetris pieces, don’t make things any easier.

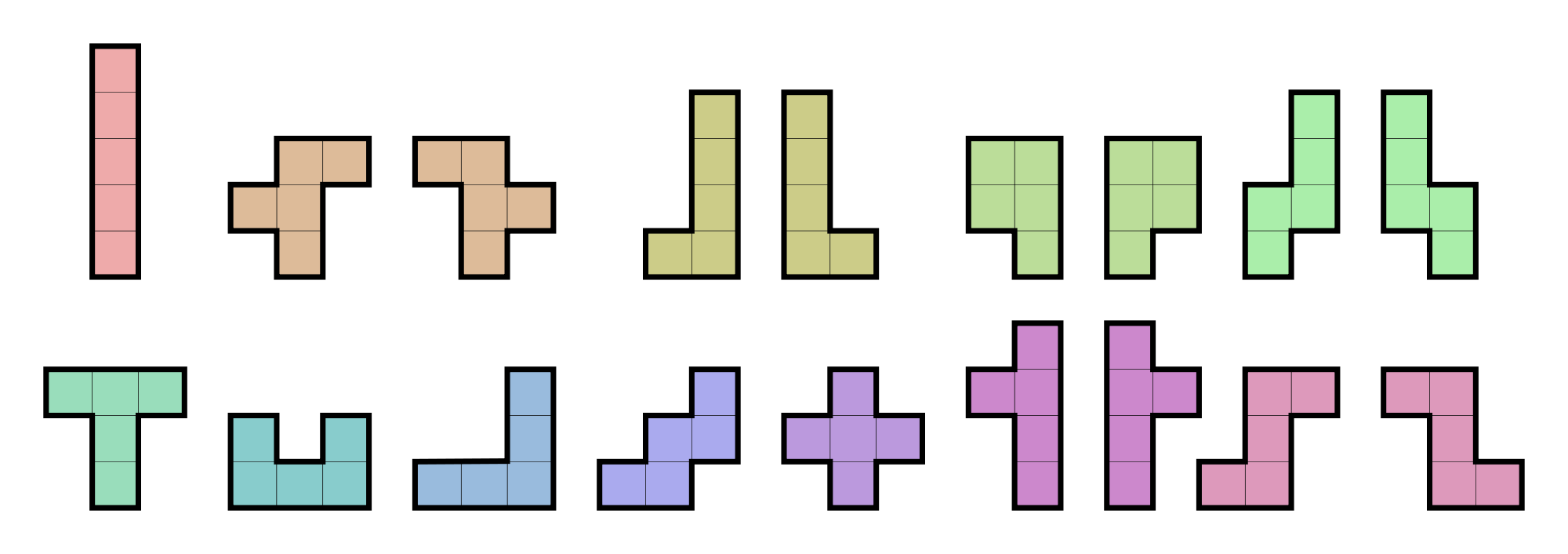

And when it comes to five-syllable words, well, they’re about as much fun as toothpaste with orange juice.

And if you were to be saddled with one or two of these in a Tetris game, you might be able to get by.

But the game just wouldn’t be fun anymore if you were to be handed huge pieces like these over and over and over.

PlainLanguage.gov also has a super handy list of simple words: bit.ly/plainwords

That takes you from 3 syllables… to 2.

“Start your screen reader prior to the test.”

That takes you from 2 syllables… to 1.

“We will commence testing on Tuesday.”

That takes you from 3 syllables… to 2.

“The nav bar doesn’t have sufficient contrast.”

That takes you from 4 syllables… to 1.

“Enable grayscale mode in order to see the page without color.”

That takes you from 4 syllables… to 1.

“This link isn’t focusable.

Consequently, it isn’t accessible.”

That takes you from 4 syllables… to 1.

“Use the guidelines in the following table:”

“The widget supports the following keyboard shortcuts:”

That takes you from 3 syllables… to 1.

“That works in JAWS.

However, it doesn’t work in VoiceOver.”

But when it comes to syllables,

That takes you from 2 syllables… to 1.

That takes you from 2 syllables… to 1.

COCA is a database of 450 million words from 1990 to 2012 covering sources including newspapers, magazines, and TV transcripts.

Here’s what Tom discovered across his analysis of newspapers and magazines in particular:

| contraction | use in newspapers & magazines |

|---|---|

| don’t | 7.7 times more often than “do not” |

| can’t | 2.9 times more often than “cannot” |

| doesn’t | 2.8 times more often than “does not” |

| didn’t | 2.7 times more often than “did not” |

| won’t | 2.6 times more often than “will not” |

The tide has turned.

People who study linguistics, such as Wayne Danielson and Dominic Larosa, found out decades ago that contractions improve readability.

Danielson, W. A., & Larosa, D. L. (1989). A New Readability Formula Based on the Stylistic Age of Novels. Journal of Reading, 33(3), pp. 194, 196.

Most types of writing benefit from the use of contractions. If used thoughtfully, contractions in prose sound natural and relaxed and make reading more enjoyable.

photo: Attack, Robot (cc) Jeremy Keith

I will be glad to see them if they do not get mad.

I’ll be glad to see them if they don’t get mad.

They do that because screenwriters know that the easiest way to make anyone sound like a robot is to take away all their contractions.

So the next time you’re writing something for a client, ask yourself this:

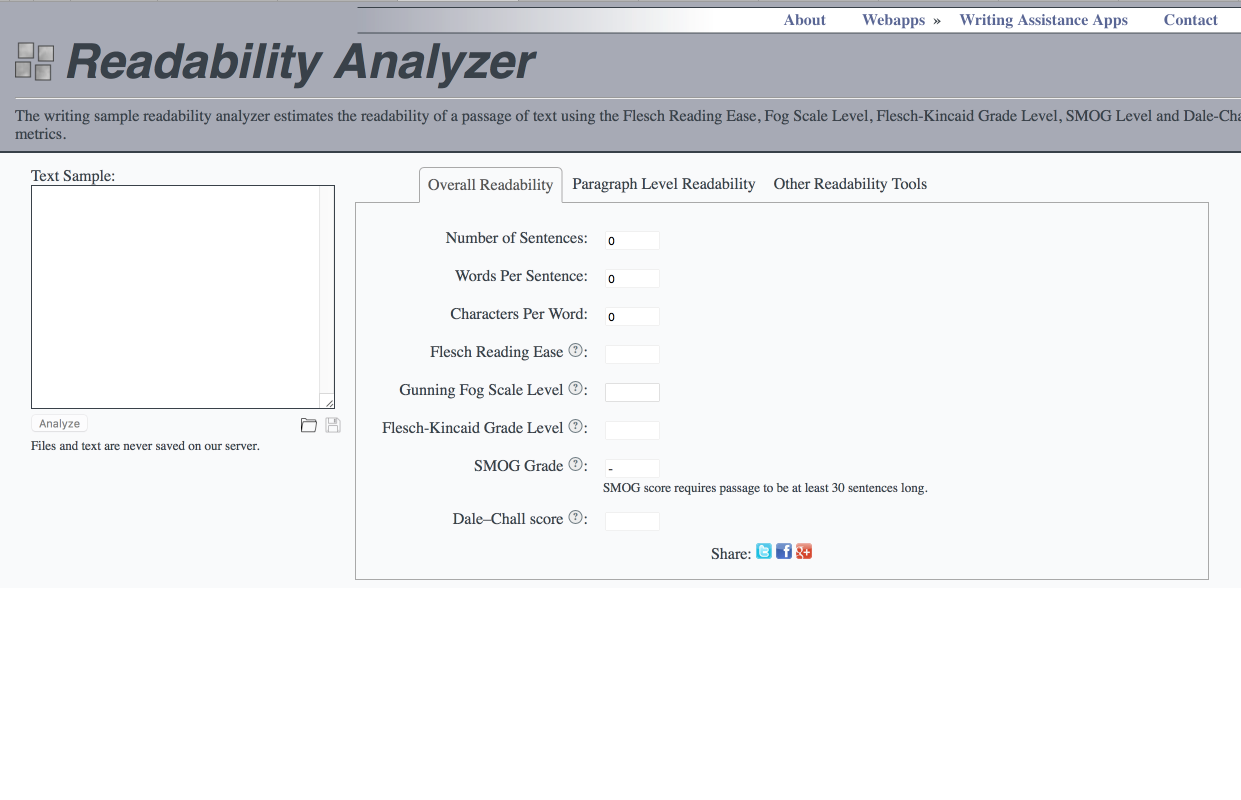

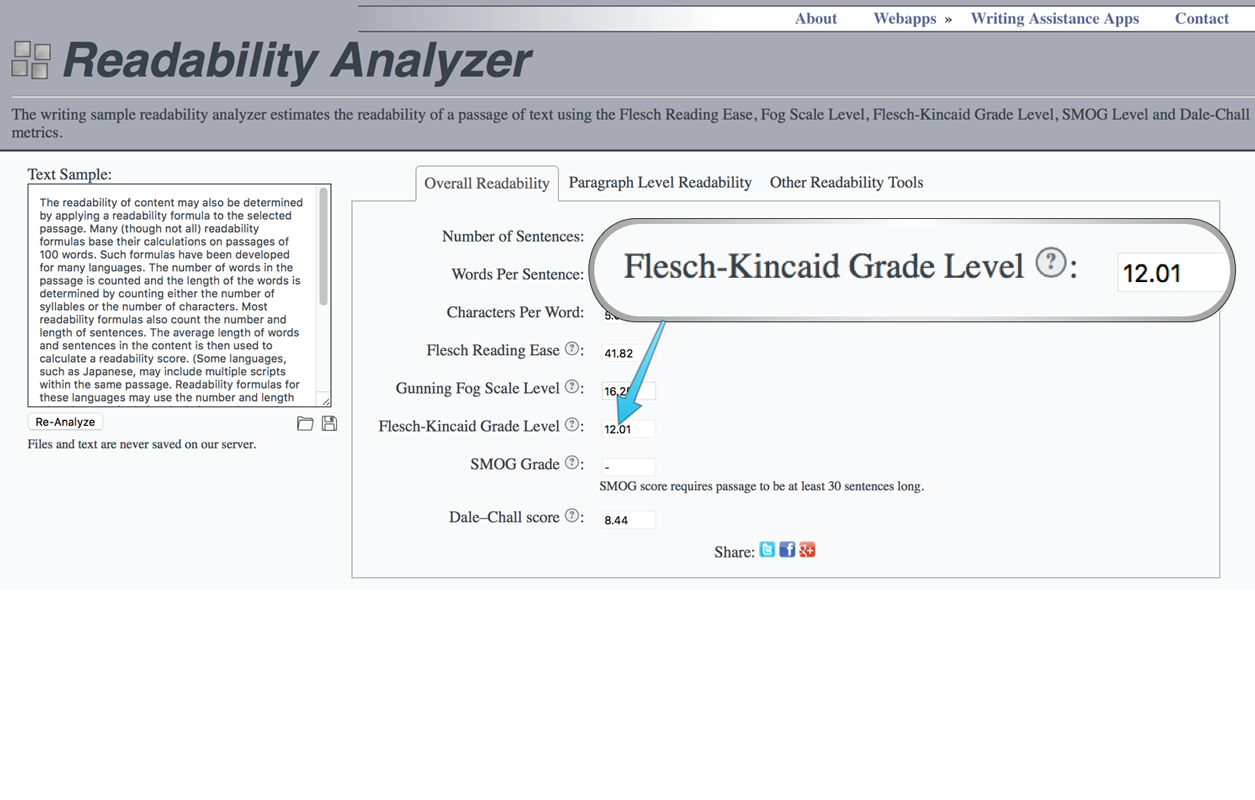

Readability Analyzer: bit.ly/readinganalyzer

Once you’re at the Readability Analyzer, paste your content into the text box, and the site will calculate your text’s readability numbers.

To follow WCAG 3.1.5, aim for a Flesch-Kincaid reading-grade level less than 9.

Looks like WCAG doesn’t fare too well.

a11y: @HandCoding / words: @FriendlyAshley